A tie-up is like a pizza: the bigger it is, the more slices you can chop it into.

A tie-up is also like a pizza in that you can put different toppings on each slice. (I know that sounds like a stretch, but bear with me.)

In the What is Twill? course, we discussed that regular twill tie-ups have the same ratio on every treadle, which is to say that every treadle has the same pattern of black and white squares, just shifted up or down one compared to its neighbors. Also, because every treadle is the same, we only have to consider a single treadle to get the full picture.

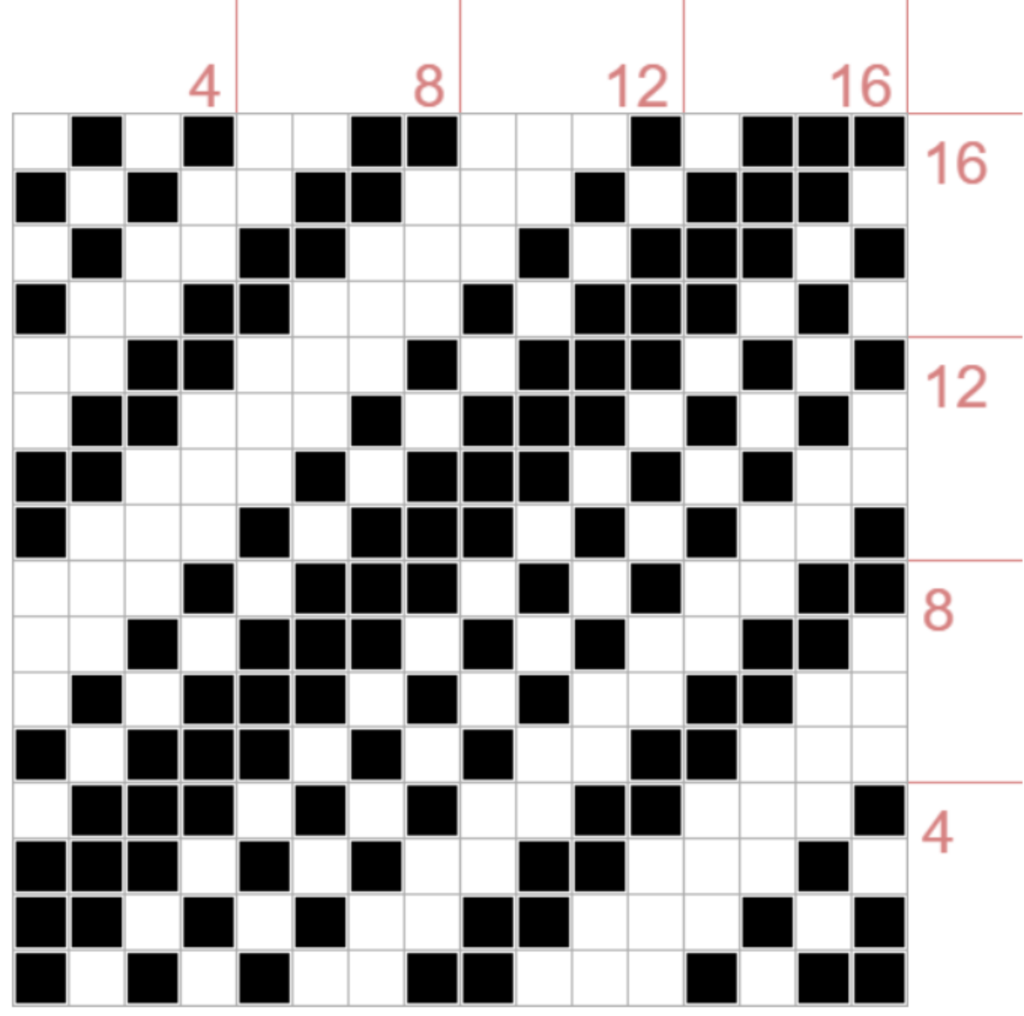

Let’s go big and look at a 16 shaft tie-up. In fact, we only need to look at a single 16S treadle, since all the other treadles will look the same.

Here it is:

Doesn’t look like much, does it? That’s because it hasn’t got any toppings on it yet! (I’m committing fully to this analogy.)

Even though it’s topping free, let’s cut it up. For the moment, we’ll cut it vertically into four equal pieces of four shafts each:

Now for the toppings! With four shafts, we’ve got several options for what to put on each piece.

We could top it with two different flavors of plain weave:

We could top it with four different flavors of 2/2 twill…

…or of 1/3 twill…

…or of 3/1 twill:

That gives us 14 different choices of toppings for each of the four pieces. We can only put one topping on each piece, but there’s no reason we can’t put the same topping on more than one.

Which ones should we pick? Rather than agonize over this all day, I’m just going to take the first one from each group – that way I at least get a variety of toppings.

Okay, so the first choice from each group looks like this:

From bottom to top, that’s 3/1, 1/3, 2/2, and 1/1/1/1.

If we glue the pieces back together into a single treadle, we’ve got this:

Which, unsurprisingly, has a 3/1/1/3/2/2/1/1/1/1 ratio.

To be clear: I could have chosen any other combination of toppings and put them on the pieces in any order. I could have chosen more than one from a group, or chosen the same one more than once. I could have put them on the pieces from bottom to top instead of top to bottom, or mixed them up in a different way. If I’d done something different, the reassembled treadle would have a different ratio.

Now let’s turn the one reassembled treadle into a complete, regular twill tie-up:

Notice that the first column looks just like our treadle and the top row looks just like our treadle tipped onto its side. The whole tie-up has the same ratio as the single treadle.

Did you notice I was careful to talk about “pieces” of the treadle earlier rather than “slices”? That’s because, when you slice up a tie-up according to which toppings are on each slice, you have to do it diagonally. You won’t get the full effect on a treadle: you need the whole tie-up.

Now that we have the complete tie-up, I can cut it into tasty, tasty slices by structure (aka toppings), like so:

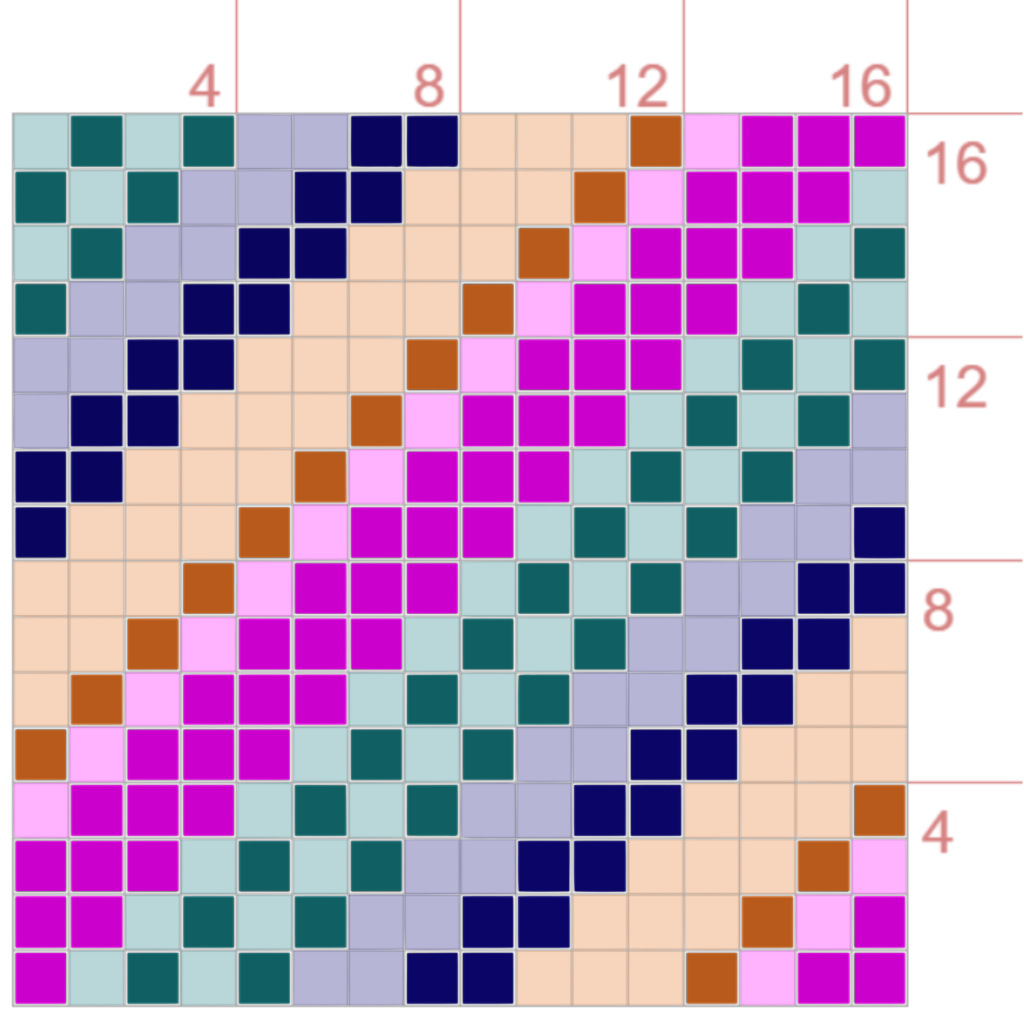

The 3/1 twill slice is in pink, the 1/3 slice in orange, the 2/2 slice in blue, and the plain weave slice in teal. Isn’t it delicious?

Since the drawdown of twill with a straight threading and treadling is just a bunch of cookie cutter copies of the tie-up…

…that means the whole fabric consists of diagonal slices of 3/1, 1/3, 2/2 twill and plain weave.

That makes it very pretty!

It also gives the fabric properties of each structure in various places. For example, it means that the ideal sett for this twill is the sett for 3/1, 1/3, 2/2 and 1/1/1/1 in each respective slice.

But wait: 3/1, 1/3, and 2/2 all like the same sett more or less, but 1/1/1/1 (aka plain weave) doesn’t! Which means that the perfect sett for this fabric might be smidge more open than whatever you’d choose for the twills. On the other hand, the plain weave is only 1/4 of the tie-up (just four shafts out of 16), so that smidge really will be a smidge.

Toppings can blend together

When you order different toppings on part of a pizza, they can leak across the boundaries and blend together. Maybe you asked for tomato sauce on one half and pesto on the other, and where the two halves meet you wind up with basil tomato pesto sauce.

The same thing can happen in a tie-up.

I happened to pick four toppings that had black on the bottom and white on the top and that meant the slices stayed distinct. If I’d made another choice, that might not have been the case.

If I’d chosen the second flavour of 2/2 twill rather than the first, for instance, my treadle would have looked like this instead:

Now instead of 3/1/1/3/2/2/1/1/1/1 I’ve got 3/1/4/2/1/1/1/1. I’ve got fewer interlacements and a float that’s 4 long.

There’s nothing wrong with that, it’s just different. In particular, the ideal sett for this fabric might be different, since fewer interlacements and longer floats are both things that add up to more ends per inch.

A variety of toppings = shading

Topping your treadle pieces with different float lengths means you get a variety of stripe widths in the fabric. I’m not talking stripes aka slices of structure here, I’m talking actual stripes made up of floats of blue warp and white weft.

Bigger numbers in the tie-up ratio mean longer floats and therefore wider stripes. Smaller numbers in the tie-up ratio mean shorter floats and narrower stripes. Narrower stripes of warp and weft blend together optically into a middle value, whereas longer floats of warp and weft tend to keep their original value. A combination of float lengths means you get a combination of values and therefore shading.

The presence or lack of shading depends on the toppings you pick for your tie-up: If you want shading, choose toppings with a variety of float lengths. If you want uniformity, choose toppings with the same float lengths.

Whichever you want, pay attention to how the toppings blend together where they meet!

Serving size

I decided to divide my 16S treadle into four equal “servings” of four shafts each and top each piece with plain weave or a four shaft twill. That’s not the only option.

I could have divided it into servings of three shafts and topped each with plain weave or a three shaft twill. (But then I’d have to decide what to do with the extra shaft. Leave it out and just weave a 15S twill? Make one of the slices bigger than the others? Either would work.)

I could have divided it into servings of five shafts and topped each with plain weave or a five shaft twill. (I’d still have to deal with the extra shaft and would have the same options.)

I could have divided it into unequal servings: two three shaft pieces, two four shaft pieces and one two shaft piece, for instance.

To be honest, unless I’m designing a tie-up for block twills, advancing twills, or a networked draft – all cases in which treadle serving size is actually important – I don’t usually bother dividing my treadle into pieces before topping it. I just start clicking from bottom to top and make sure not to put too many black or white squares in a row.

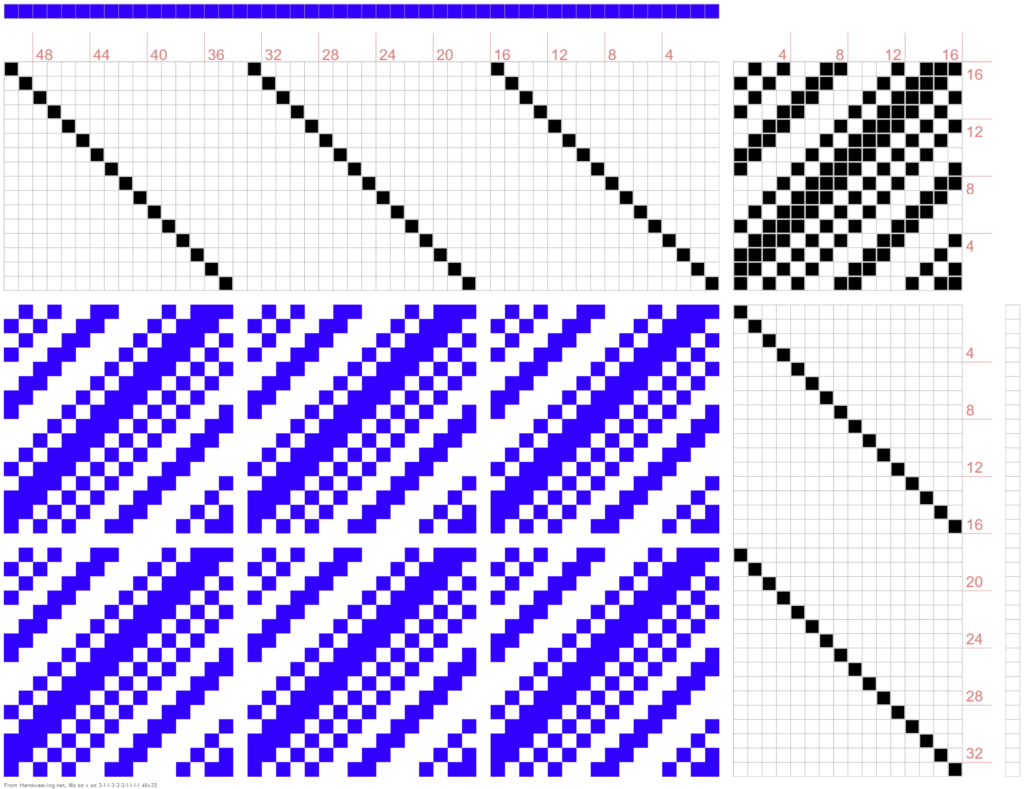

Bigger tie-ups mean more toppings and more choices…

Since tie-up slices only get one topping, more slices = more toppings = more variations in structure and shading within your tie-up and your cloth.

I already said this, but the bigger your pizz– er, tie-up is, the more slices you can cut it into. Ergo, bigger tie-ups can have more variations in structure. As you might expect, smaller tie-ups can’t.

You can’t get any variety to speak of in a 4×4 tie-up (not of the sort we’re talking about, anyway), and you’re still pretty limited in an 8×8 one.

…but tie-ups don’t have to be square!

Having only four shafts doesn’t mean you’re limited to four treadles! You can have a little more variety in a 4×6 tie-up, and a lot more in a 4×14 tie-up. Don’t have 14 treadles? Who cares! Tie up your loom directly and step on combinations of treadles to get different ratios.

A direct tie-up won’t work on an eight shaft loom with lamms and treadles, but you can still use tie-ups that are much wider than 8 treadles if you have a table loom or dobby (or are willing to get down and change the tie-up as needed).

This is what the course Shaded Twills is all about!

One big caveat, however: you do need a square tie-up to get continuous, uninterrupted slices of structure and shading that run all the way across and down your fabric in diagonals, as in the 16S drawdown above. With a shaded tie-up of the sort in Shaded Twills, you’ll get fewer different ratios across the width of the fabric (however many the height of your tie-up can accommodate) and stripes with different shading down its length. The overall effect will be weftwise stripes of structure rather than the diagonal ones you get from a square tie-up.

All the toppings go into the fabric

A tie-up is NOT like pizza in one important way: you get all the toppings you ordered whether you like it or not. You can cut a pizza apart and just eat the toppings you like, so if your friend likes hot peppers but you don’t, you can avoid them.

The tie-up and even the drawdown are not the end result of a draft, though, the fabric is. You may be able to slice the tie-up and drawdown into diagonal bands of distinct and separate structures, sure. Unless you’re willing to cut your fabric up along those same diagonals, though, every piece of fabric is going to have all of the toppings you ordered all the way across the width and all the way down the length.

Which is to say: every weftwise and warpwise section of fabric will have hot peppers, so you’d better make sure you like them.

From the Course Catalog:

Designing in the tie-up: Cookies and Clocks – Dive into all the nitty gritty detail to help you harness the potential of a straight threading and treadling by altering the tie – up.

What is Twill? – This class breaks down what makes a twill a twill, and discusses many of the twill variations that are commonly used.